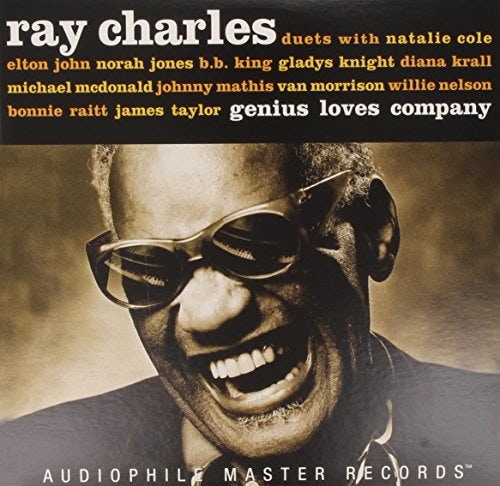

The massive commercial success of the album (over 5.5 million copies were sold worldwide up to 2007) was attributed in part to it being distributed and promoted via Starbucks coffeehouses, as well as the distribution and marketing relationship between Concord Records and the Starbucks Hear Music label. By the first month of its release, the album had shipped over two million copies in the United States and shipped more than three million worldwide, receiving gold, silver and platinum certifications across North America, Europe and several other regions.

Genius Loves Company also received a significant amount of airplay on jazz, blues, R&B, urban contemporary and country radio stations, as well as critical praise from well-known publications and music outlets. Within its first week of release, the album sold over 200,000 copies in the United States alone, while it debuted at #2 on the Billboard 200 chart, eventually ascending to #1 on March 5, 2005, becoming Charles' first #1 album since Modern Sounds In Country And Western Music in 1962. The release of Genius Loves Company served as Charles' two-hundred fiftieth of his recording career, as well as his last recorded effort before his death on June 10, 2004. Genius Loves Company proved to be a comeback success, in terms of sales and critical response, quickly becoming Charles' first top-10 album in forty years and the best-selling record of his career. No wonder they called him a genius.Ĭhicago, Illinois PLUG IT IN! TURN IT UP! Electric Blues 1939-2005.The release of Genius Loves Company was preceded by a period of mostly mediocre LP releases by Charles and critical slide after the massive success of his 1962 crossover opus Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. Of course, Ray's ceaseless musical experiments rendered him a superstar right up to his Jdeath. And so, as would be the case with many other sessions, when there had to be some direction from us because we weren't going anywhere, or some changes to be made, that wasn't the case with Ray." I mean, there was never anything negative or worrying, because Ray Charles had the whole thing figured out from beginning to end. "They were exciting, edifying, thrilling," said Wexler. His sessions were like no other at Atlantic. There Ray would transform R&B with his daring gospel/blues synthesis on the smashes I've Got A Woman, Hallelujah I Love Her So, and What'd I Say (speaking of advancements in electric instrumentation, he played a Wurlitzer piano on the latter). Swing Time was experiencing financial difficulties in 1952, so Lauderdale peddled Charles' contract to Atlantic. His first release was a hit and two more after that too, though his predilection for imitating Nat King Cole and Charles Brown hadn't been tamed yet. Jack Lauderdale of Swing Time/Down Beat Records brought Charles and his McSon Trio aboard in 1949. He left the state school for the blind at 15, his piano skills already formidable, and somehow made his way cross-country from Jacksonville, Florida to Seattle.

"We got the backing musicians, we got the arranger Jesse Stone, we rehearsed, and so on."īorn in Albany, Georgia on Septembut raised in Greenville, Florida, Ray Charles Robinson lost his sight as a child but gained a love for music-blues, boogie-woogie, jazz, country-that was unshakable.

"He still was being recorded in the conventional way, like you'd record almost any single singing artist," said Ray's late co-producer, Jerry Wexler. Ray had yet to explode with his groundbreaking gospel/blues synthesis, although his impassioned vocal and two-fisted piano offered clues as to his immediate future. Brother Ray didn't use a guitarist on his subsequent Atlantic sides, making Baker's presence quite unusual (arranger Jesse Stone wrote the song under his alias of Charles Calhoun). Ray Charles had only recently joined the roster of Atlantic Records when he waxed the mournful blues Losing Hand on with a New York session crew consisting of saxists Dave McRae, Freddie Mitchell, and Pinky Williams, bassist Lloyd Trotman, drummer Connie Kay, and guitarist Mickey Baker, whose slippery chords cascade downward like thick, murky molasses.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)